Once eaten by a human, the L3 larvae try to complete their life cycle by burrowing into tissue out of the intestines to get to the brain, traveling either through the blood or along nerves. The migration along nerves can cause sensory abnormalities, like burning, tingling, or pain. Once in the central nervous system, the invasion can cause confusion, encephalopathy, seizure, cranial neuropathy, or eye problems. In a brain, the L3 larvae would normally develop into young adults, but human brains are dead ends for the worms, which eventually die there without fully maturing.

Some of the luckiest rat lungworm victims don’t need treatment and make full recoveries after the larvae die off on their own. But the woman in this case was not so lucky. Her doctors noted in their report that the worms typically stay in the pia mater of the brain, a delicate innermost layer of tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. They rarely cause lesions in the white matter, a deeper tissue containing nerve fibers that transmit signals between different parts of the brain.

Li et al, JAMA Neurology 2025

Li et al. JAMA Neurology 2025

Li et al, JAMA Neurology 2025

Li et al. JAMA Neurology 2025

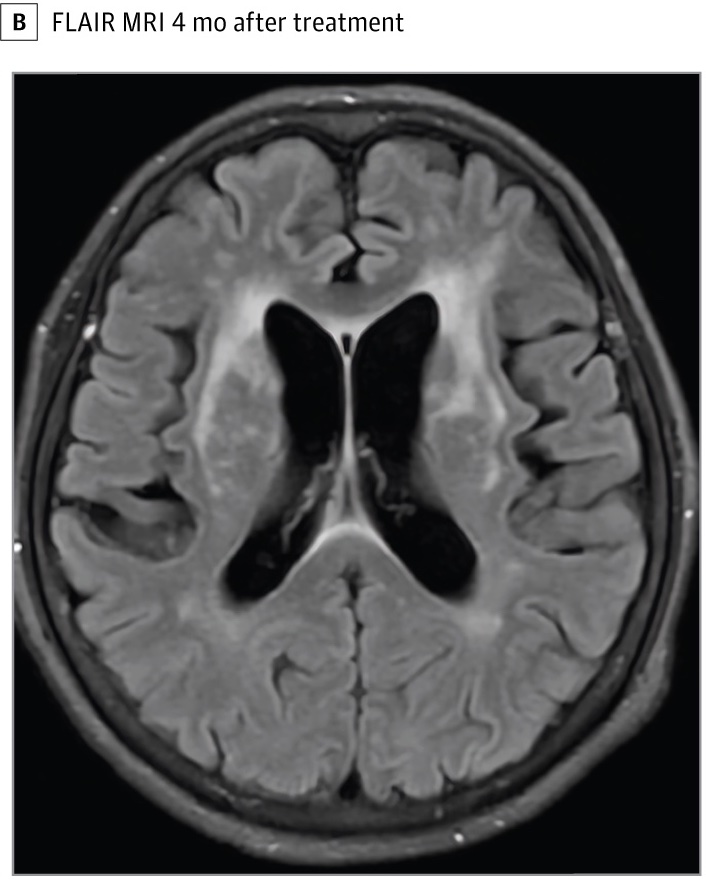

In her case, the worms appeared to be directly and actively invading her white matter, which was captured by the FLAIR MRIs. The lesions progressed “rapidly” in the three days after eating the uncooked crayfish and the two weeks when she was misdiagnosed and treated for a bacterial infection (labeled as “after treatment” in the second image). The authors noted that the lesions looked significantly different from the lesions seen when white matter is damaged from a lack of blood flow, such as in a stroke. This “may be related to direct invasion of A. cantonensis or inflammation of small vessels,” they speculated.

While there isn’t a clearly defined standard treatment for such infections, the doctors started the woman on an anti-parasitic drug called albendazole, which is often used. After two weeks, her symptoms improved, and she was able to communicate again. After four months, a third FLAIR MRI showed a “significant reduction” in white matter lesions. It’s unclear, however, if she made a full recovery.