There have also been several studies examining the effects of social interdependence and similar social contexts on children’s ability to delay gratification, using variations of the marshmallow test paradigm. For instance, in 2020, a team of German researchers adapted the classic experimental setup using Oreos and vanilla cookies with German and Kenyan schoolchildren, respectively. If both children waited to eat their treat, they received a second cookie as a reward; if one did not wait, neither child received a second cookie. They found that the kids were more likely to delay gratification when they depended on each other, compared to the standard marshmallow test.

An online paradigm

Rebecca Koomen, a psychologist now at the University of Manchester, co-authored the 2020 study as well as this latest one, which sought to build on those findings. Koomen et al. structured their experiments similarly, this time recruiting 66 UK children, ages 5 to 6, as subjects. They focused on how promising a partner not to eat a favorite treat could inspire sufficient trust to delay gratification, compared to the social risk of one or both partners breaking that promise. Any parent could tell you that children of this age are really big on the importance of promises, and science largely concurs; a promise has been shown to enhance interdependent cooperation in this age group.

Koomen and her Manchester colleagues added an extra twist: They conducted their version of the marshmallow test online to test the effectiveness compared to lab-based versions of the experiment. (Prior results from similar online studies have been mixed.) “Given face-to-face testing restrictions during the COVID pandemic, this, to our knowledge, represents the first cooperative marshmallow study to be conducted online, thereby adding to the growing body of literature concerning the validity of remote testing methods,” they wrote.

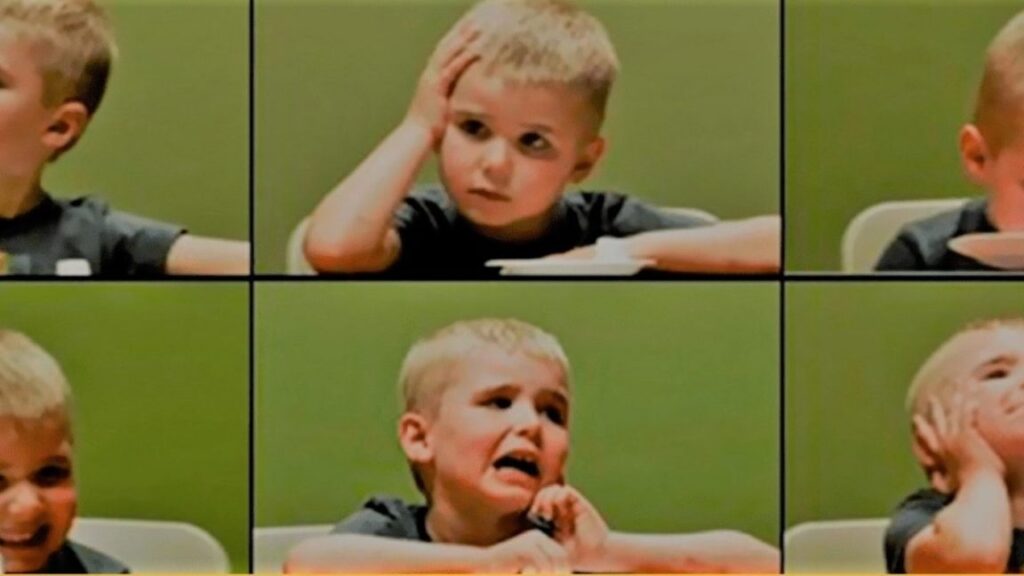

The type of treat was chosen by each child’s parents, ensuring it was a favorite: chocolate, candy, biscuits, and marshmallows, mostly, although three kids loved potato chips, fruit, and nuts, respectively. Parents were asked to set up the experiment in a quiet room with minimal potential distractions, outfitted with a webcam to monitor the experiment. Each child was shown a video of a “confederate child” who either clearly promised not to eat the treat or more ambiguously suggested they might succumb and eat their treat. (The confederate child refrained from eating the treat in both conditions, although the participant child did not know that.)