Credit:

Richard Nyberg, USAID

Another major hot spot is the heavily contaminated Biên Hoà airbase, where local residents continue to ingest high levels of dioxin through fish, chicken and ducks.

Agent Orange barrels were stored at the base, which leaked large amounts of the toxin into soil and water, where it continues to accumulate in animal tissue as it moves up the food chain. Remediation began in 2019; however, further work is at risk with the Trump administration’s near elimination of USAID, leaving it unclear if there will be any American experts in Vietnam in charge of administering this complex project.

Laws to prevent future ‘ecocide’ are complicated

While Agent Orange’s health effects have understandably drawn scrutiny, its long-term ecological consequences have not been well studied.

Current-day scientists have far more options than those 50 years ago, including satellite imagery, which is being used in Ukraine to identify fires, flooding, and pollution. However, these tools cannot replace on-the-ground monitoring, which often is restricted or dangerous during wartime.

The legal situation is similarly complex.

In 1977, the Geneva Conventions governing conduct during wartime were revised to prohibit “widespread, long term, and severe damage to the natural environment.” A 1980 protocol restricted incendiary weapons. Yet oil fires set by Iraq during the Gulf War in 1991, and recent environmental damage in the Gaza Strip, Ukraine, and Syria indicate the limits of relying on treaties when there are no strong mechanisms to ensure compliance.

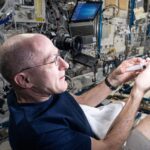

Credit:

USAID Vietnam

An international campaign currently underway calls for an amendment to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to add ecocide as a fifth prosecutable crime alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression.

Some countries have adopted their own ecocide laws. Vietnam was the first to legally state in its penal code that “Ecocide, destroying the natural environment, whether committed in time of peace or war, constitutes a crime against humanity.” Yet the law has resulted in no prosecutions, despite several large pollution cases.

Both Russia and Ukraine also have ecocide laws, but these have not prevented harm or held anyone accountable for damage during the ongoing conflict.

Lessons for the future

The Vietnam War is a reminder that failure to address ecological consequences, both during war and after, will have long-term effects. What remains in short supply is the political will to ensure that these impacts are neither ignored nor repeated.![]()

Pamela McElwee, Professor of Human Ecology, Rutgers University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.